Earlier this year, IHUK Chairman Richard Grieveson gave a series of presentations to key stakeholders that gave a view into his vision of the future of the sport in Britain.

The presentation delivered to team owners under the EIHA umbrella contained some very promising proposals for both the clubs and the national programme.

The opening segment regarding the Talented Athlete Development Pathway, describes a route from beginning to U20 level.

This would be guided from the lowest rung of junior hockey by a National Talent Development Officer, and up to the senior GB team by the National Head Development Coach.

There is also mention of an IHUK National Coach Education Programme. The leader for this role is the person who’ll have the greatest impact on the sport and will need to be recruited very carefully – a point we’ll look at later.

The pathway route is fairly straightforward except for one new feature which is greatly encouraging to see included.

The personnel for the GB senior team will be made up of the Head Coach, an Assistant Coach, and the Head Coach of the U20 side. This is replicated for the remaining age levels.

Why is this important? All levels under the senior national team are essentially developing their players for the next level – this also holds true for the domestic leagues.

For the GB U20 boss to develop players to step up to senior level, they must be involved with the senior team.

It mainly means both coaches and players will better understand what’s expected of them at the next stage in their career and in theory should leave them much better prepared.

This is replicated at the age groups below, and is a model that’s easy to adapt and adopt elsewhere. However, this is just one cog in the system.

The presentation goes on to discuss the Elite League, asking whether this is the pinnacle of the domestic sports development continuum.

While the accompanying notes are unavailable, the tone of the rest of the presentation appears to suggest that it isn’t.

We can liken this to a mountain range – each one is huge to climb, but once you get to the top you realise there are greater peaks still to climb.

Some players, after juniors, will just play for the fun of it, some may venture into the foothills and smaller peaks of the NIHL, some will attempt the challenging peaks that are the EPL, and fewer still will look to the tougher ranges of the EIHL.

However, there are larger mountains in Europe, and eventually, there are the brave few that look to the killer mountains – the places where few dare to tread and even fewer succeed – the North American leagues such as the ECHL, AHL or the big one, the NHL.

Getting Brits into the NHL is obviously not practical at this stage, but as aims go – go big, or go home!

From here we move onto the lower tiers and the heart of the presentation. The proposal is nothing if not ambitious, however it appears to be an achievable ambition.

The proposed second tier

“To develop and operate a new, sustainable and fit for purpose league at tier two level within the UK (replacing the EPL) which is operated by the NGB in partnership with a League Management Committee.

“The League will provide development opportunities for British Athletes, Coaches and Officials, supporting them to achieve their maximum potential and in doing so playing a pivotal role in developing the sport throughout the UK.”

A UK-wide league as opposed to just English is proposed, meaning greater involvement from Scottish clubs. There would be around 20 teams split into two to four conferences.

In isolation, this could appear to be little more than rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic, but the introduction of a player points cap on the entire roster is one that will help drive development and takes the proposal to a whole different level.

The points values are as follows:

ITC – 4 points

British trained players:

Aged 28 and over – 3 points

Aged 24-27 – 2 points

Aged 20-23 – 1 point

Under 20 – 0 Points

British trained netminders under 25 – 0 Points

There are also mandatory minimum roster sizes – in year one, a minimum of 14 + 2 including five ITC players, 16 + 2 including four ITC players in year two and 17 + 2 including four ITC players in year three.

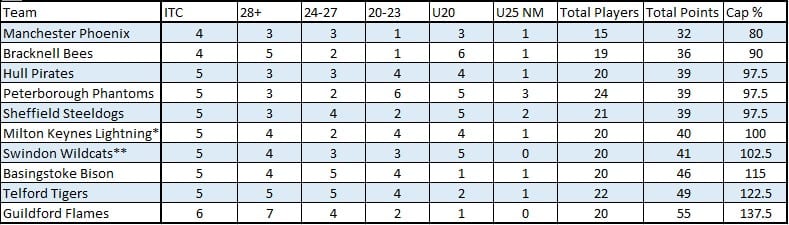

The player cap is set provisionally at 40 points. Using Elite Prospects and removing players who have been released gives the following:

* Mikolay Lopuski is long term injured and not counted

** Aaron Nell and Toms Rutkis are long term injured and not counted

The majority of teams are on or under the cap, with a small minority requiring any significant change in their rosters.

Running NIHL1 South teams Chelmsford Chieftains and Invicta Dynamos through the same cap produced 38 and 40 points respectively.

These points do not measure the quality of the player or the overall standard of the team, however age and ITC status are probably the most transparent measurements.

Something else from this portion of the presentation that’s promising is the clear intention to reduce the number of ITC players in the second tier – this opens up a slot in each team for a British trained player – up to 20 slots across the league.

Combined with the increasing minimum size, this creates many opportunities for a greater flow of younger players into higher leagues.

The points cap, which is not a wage cap, will also aid stability for the teams and the league. Wage caps are difficult, if not impossible to enforce, but this points cap is so simple anyone can follow it.

There is much that is positive in this presentation, but there’s one thing mentioned above that will probably fly under the vast majority of people’s radar.

IHUK National Coach Education Programme

This will come under the purview of the GB Programme Management Board. Any study into comparisons between GB and more successful hockey nations will find two important differences.

While greater availability of facilities is beyond the control of the NGB, the standard of coaching is entirely within its remit.

Something that cannot be ignored is the vast majority of coaching in this country is carried out by unpaid volunteers.

These people are the reason we have any development in the sport at all. They are the backbone of the sport, capturing juniors’ interest and setting the foundations.

Essentially, this programme should be about helping the coaches, especially junior coaches, to improve their coaching skills.

That’s not saying they’re not good at what they do – every player that’s come through the junior system that’s gone to the NIHL, EPL, EIHL, to Europe or North America to play is proof they’re doing the very best they can.

The purpose of this programme should be help them do the good work they do even better.

So why junior coaches over the national team or league teams? If you improve the standard of the GB national coach you help to improve 20 or so players, but improve the standard of U9 coaches and you help to improve thousands of players.

It won’t just be restricted to U9 coaches, that would be a stupid idea, but it will give far more emphasis to the younger age group coaches because the cumulative impact will be immense.

At this point, there’s the danger of getting on a high horse with regards to player development at higher levels and with good reason – player development is a constant and vitally important process.

While some people have argued ‘what happens if we develop these players and they leave?’ we should flip this around and ask ‘what happens if you don’t develop them and they stay?’

If the coach education programme is implemented and supported properly – it won’t be cheap, but the good things in life never are – and used properly by the coaches, this will be probably the greatest single step forward for the British game in, well, forever.

This brings us to probably the biggest problem with this role.

There currently isn’t anyone in our game at this point with the experience and knowledge to carry it out to the level required.

Whoever takes it is going to have to tell some very inconvenient truths which would probably be better delivered by someone from outside the current system.

The same thing has happened at club level – existing volunteers and employees of a club try to get some basic changes made to the off ice-set up and are rebuffed.

An outsider with a strong hockey pedigree says exactly the same thing and it’s accepted instantly. It’s frustrating to say the least, but the benefits make it worthwhile.

The head of this programme is a massively important role and must be recruited very, very carefully. The successful applicant will need to have experience of managing stakeholders at all levels, and MUST as a very basic minimum, have the full, unqualified support of the NGB.

They need to have experience of overhauling an education programme, be able to identify strengths as well as weaknesses, have a clear history of success and legacy building, and they MUST be able to explain ‘WHY’ repeatedly and show a lot of patience.

After reading all this you’ll probably be asking yourself ‘if there’s so much good from this, what are the downsides?’

Hockey fans are a hard-bitten bunch, often looking for the downside, the catch, the small print, and there is one – what will the top tier be doing to support this, and/or, what will the NGB be doing to encourage, persuade or even order the top tier to do that?

The top tier should be actively supporting this entire programme – the restructured second tier, identifying and developing talent, amendments to the GB structure, the coaching improvement plan, from, if nothing else, simple self-interest.

An often-cited complaint from within the EIHL is that British players coming through are not good enough or too expensive.

Supporting this programme will help to resolve this in a great way. The availability of the British players of a standard to enter the EIHL needs to increase – doing so will help to drive the wage demands down because they’ll no longer be a rare commodity.

However, the EIHL teams must continue to develop players themselves too – train their third line to play second line, their second to play first line and promote from within.

By doing this, it will reduce player wage demands, improve the quality of the players coming up and increase the pool of players capable of playing for GB.

To summarise, this is a very positive, innovative presentation which should be giving everyone involved in hockey a great deal of optimism.

In some ways, it feels like the equivalent of embarking on the Starship Enterprise – getting ready to boldly go where no man has been before!

We’re not though – we’re boldly going where we should have gone years ago, where most other hockey nations have been before, repeatedly and shown the benefits. Still, better late than never.

However, that should not take away from what Grieveson and his team are trying to achieve.

We want stability, we want progress, we want to watch the best players we can at an affordable price and know that our team will be here next week, month or year and this plan is about the best chance we have for seeing this.

Since delivering the presentation the IUHK boss has developed his model further. He’ll be discussing this with BIH in the coming days and we’ll bring you the interview in due course.

(Image permissions: Tony Sargent, Scott Wiggins and Karl Denham)

Mark Gordon

2nd December 2016 at 7:47 pm

Why not the NHL? Uk has over 12000 registered hockey players. Denmark has 4500 players and had 3 players drafted to NHL last year. Is this just a lack of ambition?

Dan Breen

2nd December 2016 at 8:03 pm

I think when we have the structure and philosophy of continuous development then I see no reason why not.

Ambition supported by infrastructure.